How Are Immigrants Treated in Czech Republic + Peer Reviewed Scholarlly

- Research article

- Open Access

- Published:

A systematic review of working conditions and occupational health among immigrants in Europe and Canada

BMC Public Wellness volume 18, Article number:770 (2018) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

A systematic attempt to summarize the literature that examines working conditions and occupational health amidst immigrant in Europe and Canada.

Methods

We established inclusion criteria, searched systematically for articles included in the Medline, Embase and Social Sciences Citation Alphabetize databases in the menstruation 2000–2016 and checked the reference lists of all included papers.

Results

Eighty-two studies were included in this review; 90% were cross-exclusive and 80% were based on self-report. Work injuries were consistently institute to be more prevalent amid immigrants in studies from dissimilar countries and in studies with dissimilar designs. The prevalence of perceived discrimination or bullying was found to be consistently college amongst immigrant workers than amid natives. In general, however, nosotros plant that the bear witness that immigrant workers are more likely to be exposed to concrete or chemical hazards and poor psychosocial working weather condition is very express. A few Scandinavian studies support the idea that occupational factors may partly contribute to the higher risk of sick leave or disability alimony observed among immigrants. Notwithstanding, the testify for working atmospheric condition as a potential mediator of the associations between immigrant status and poor general health and mental distress was very express.

Conclusion

Some indicators suggest that immigrant workers in Europe and Canada experience poorer working conditions and occupational wellness than do native workers. Nonetheless, the ability to depict conclusions is limited by the big gaps in the available information, heterogeneity of immigrant working populations, and the lack of prospectively designed accomplice studies.

Groundwork

According to the International Labour System's estimates, there are 150 million immigrant workers throughout the globe, almost half of whom are concentrated in two broad subregions, Northern America and Europe. In Europe, the proportion of foreign-born residents increased by more than 50% in the start decade of 2000 because of mobility and migration, and this group now represents about 10% of the European population [i]. Immigrant workers are unremarkably defined as all economically agile immigrants because most of the data sources cannot define the reasons for migration and are probable to record only nationality or land of birth. Most immigrant workers throughout the globe are engaged in the services sector and in industries such as manufacturing, construction, transportation and agriculture [2]. New European Union (European union) and national state policies to liberalize regulations have been introduced during the last decade to open upwards labour markets in Europe, to stimulate new supply- and demand-driven forms of labour migration, and to meet labour market demands and demographic outlook. Most of the immigrant workers from inside and outside of Europe piece of work in low-skilled jobs [1]. Although both immigrant status and unskilled labour are thought to establish particular risks of unsafe and unhealthy working environment, relatively little is known near working conditions and piece of work-related wellness of migrants in host countries [3].

Paid work is important for quality of life because it provides a source of income and identity. The workplace offers opportunities for personal development and socializing [4]. Yet, non all jobs provide equal opportunities, and some are characterized by occupational hazards such as heavy concrete work, risk of injury or exposure to toxic substances or poor psychosocial working atmospheric condition (e.g., excessive mental piece of work load, depression task autonomy or negative social interactions). It is well documented that such exposures tin can negatively affect workers' wellness [5]. In destination countries, immigrant workers are reported to be over-represented in less desirable, depression-skilled jobs and are thought to be more exposed to adverse working conditions than natives [6]. Greater difficulties in entering the labour market and in validating prior educational and technical grooming once in the host land, poor language skills, and a lack of workers in some unskilled occupations may contribute to the higher rate of immigrant employment in the nigh hazardous jobs. Hence, there are reasons to assume that work-related wellness amongst the immigrant population differs from that of the native population in various countries. Other factors such equally the reason for migration, geographical origin, age at migration and residence time in the new land also likely contribute to differences in wellness condition between immigrant groups and the native population [7]; however, these topics were considered to be beyond the scope of the systematic search in present study.

More than 10 years have passed since Ahonen and co-workers published the most contempo review of research on occupational wellness amid immigrant groups [8]. Their search strategy captured both original and overview manufactures relating to the topics of immigration, work and health in the PubMed database for the period 1990–2005. Nearly xc% of the included studies were conducted in the United States, Commonwealth of australia and Canada, while only a few were conducted in Europe. The almost studied outcome noted in their review was occupational injuries, whereas studies of exposure and occupational health problems involved mainly specific populations (due east.g., farm workers and textile workers). The authors reported that the studies included were highly heterogeneous and difficult to allocate. Even so, they ended that all indicators together drew a worrying image of immigrant workers' health.

Our objective hither was to perform a systematic review of the inquiry on both working weather condition and occupational health among immigrant workers in Europe. We included studies from Canada because its clearing regime is similar to that of some European countries, specially the Scandinavian ones. We aimed to compare the human relationship betwixt working weather and occupational health in immigrant and native workers. Our main research questions were as follows:

Inquiry question one: A) Do differences in working environment and conditions exist? B) Does the human relationship between work-related exposure and health differ between these groups?

Research question 2: A) Do immigrant workers have more occupational health bug than native workers? B) Do differences pertaining to working conditions mediate differences in occupational health problems?

Methods

In this review, we defined "immigrant worker" in a full general sense as a person who is strange-built-in and economically active in the host country. Nosotros chose a broad definition to allow us to examine unlike aspects of work and health for various groups of immigrants or minorities in multiple contexts.

Search strategy

We searched systematically for the period 2000–2016 in the Medline, Embase and Social Sciences Commendation Index databases during January 2017. We limited the search to article titles and abstracts. We prepared one list of search terms related to immigration, a second related to occupational wellness or occupational exposure based on the search cord suggested by Mattioli and co-workers [9], and a third related to the land of clearing (meet Boosted file i). Other relevant sources were identified through the reference lists of all included studies and other relevant studies identified by the authors.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria and cess

Two of the authors screened the abstracts and excluded those that did not mention immigrant populations and occupational exposure or occupational wellness as key problems. All potentially relevant papers were read in total by one of the authors. If exclusion was suggested, it was confirmed by the first writer. For inclusion, studies had to meet all the following criteria:

- ane.

The study included and reported data for employed immigrants.

- 2.

The study either addressed a quantitative measure of occupational exposure or the health status of a working population or analysed the relationship between wellness and working conditions

- 3.

The study was an original study published in a peer-reviewed periodical, its abstract was reported in at to the lowest degree one of the databases.

- 4.

The study was published in English language or a Nordic language (Danish, Finnish, Norwegian or Swedish).

The included articles were assessed past one of the authors and so the main author using a ready of predefined parameters that included the study design, characteristics of the participants, definitions and measurement of working conditions and health, statistical analysis, covariates, results and limitations. This information is summarized in a table (see Additional file 2).

Results

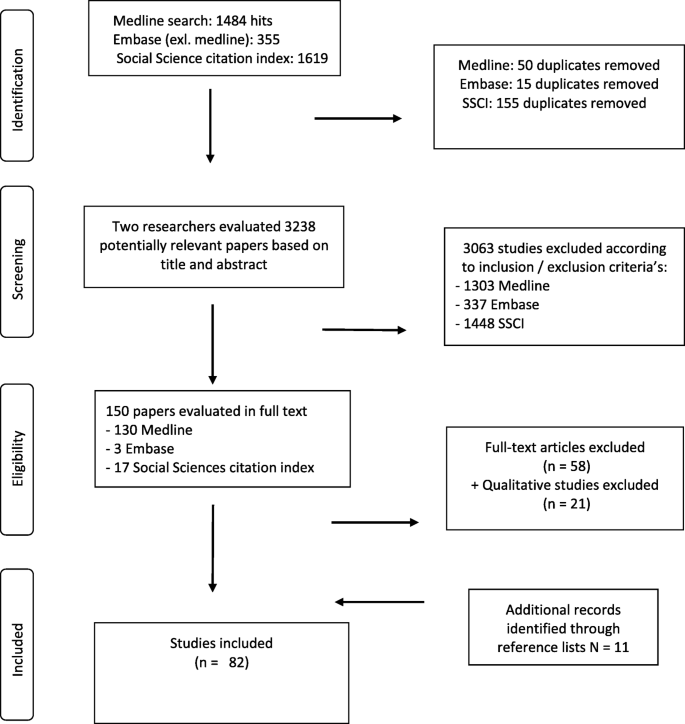

The search resulted in 3213 hits in the three databases afterwards nosotros had removed all duplicates. Nosotros excluded most of the studies (n = 3063) in the initial screening of titles and abstracts. In full, 151 manufactures were read in full, 92 of which fulfilled the initial inclusion criteria [10,xi,12,13,xiv,fifteen,16,17,18,xix,xx,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,l,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,sixty,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80]. In addition, 11 studies [81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91] identified in the reference lists were included. The excluded studies that were read in full did not report information on working conditions or wellness-related outcomes in a defined working population (n = 53); three were duplicates, and 2 were historical studies of asbestos and mesothelioma [92, 93]. Twenty-i studies [94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114] did not report relevant quantitative measures of exposure or wellness. Thus, 82 studies were included in this review (encounter the flow chart in Fig. one).

Flow chart

Virtually studies were cross-exclusive (n = 77), except for five with a longitudinal design [26, 45, 62, 70, 81]. Most studies were questionnaire-based surveys (n = 66), except for some register-based studies of sick leave or disability pension [22, 28, 37, 42, 45, 73, 81, 82] or piece of work injury [xvi, 20, 26, 29, 40, 50, 59].

The studies were from Canada (n = 13), Czech Democracy (due north = 2), Denmark (northward = nine), Finland (due north = v), Germany (n = ii), Greece (north = 1), Republic of ireland (n = five), Italy (n = ii), holland (n = 2), Norway (n = 7), Kingdom of spain (n = xx), Sweden (due north = 7), Switzerland (n = ii), the Britain (U.k.) (due north = 4), and Europe (due north = 1).

Working weather condition and their clan with wellness (n = 43 studies)

Of the 43 studies addressing working conditions, 32 addressed enquiry question 1A pertaining to differences in specific piece of work-related exposures and 17 examined inquiry question 1B on whether the relationships between specific exposures and health effects differ betwixt immigrants and natives. These results are grouped into the post-obit categories: mechanical, concrete or chemical exposures, psychosocial stressors, bullying or bigotry and unlike employment arrangements, summarized in separate tables (Tables one, 2, 3 and 4).

Mechanical, concrete or chemical exposure and health (n = 6 studies; Table 1)

A study from 31 European countries, compared immigrant workers with natives and institute that immigrant transmission workers reported higher levels of exposure to concrete factors (vibrations, dissonance and heat) and mechanical factors (painful positions, heavy loads and continuing or walking). Exposure to dust or fumes was more prevalent among female person immigrant workers only [64].

Three national surveys that compared immigrant workers to natives reported greater exposure to heavy concrete demands [33, 35, 60], and two surveys reported small and not-significant differences for lifting weights and forced work position [63] and working postures [35]. Surveys from Kingdom of spain reported greater exposure to dust among immigrant workers [33], but no significant differences for chemical exposure [63]. A survey from Canada reported lower exposure to toxic substances for immigrants [60]. A second survey from Canada reported that, both 2 and 4 years after inflow, immigrants with poorer English language skills or lower educational level or those who had immigrated to Canada as a refugee were more likely to be employed in occupations with greater physical demands compared with their previous jobs before arriving in Canada [70].

General psychosocial working atmospheric condition and health (n = eighteen studies; Table two)

Three studies reported greater task demands among immigrants [39, 46, 64], while one reported lower job demands [80], and six reported small and no meaning differences between natives and immigrants [ten, 35, 44, 53, 55, 63]. Iv studies of the general population reported lower levels of chore control in immigrant workers [35, 39, 77, 80], whereas three studies of workers within the aforementioned occupation constitute no significant differences betwixt immigrants and natives [x, 44, 53], and one study reported a meaning college level of chore control among immigrants [55]. Ii studies of the general population [39, 80] establish lower levels of social back up amongst immigrant workers, whereas a third report of the general population found no differences [35]. Iii studies that compared immigrants and natives within the same occupation constitute no differences in the level of social support from colleagues [44, 53] or perceived leadership quality [55].

Pertaining to enquiry question 1B, similar associations betwixt psychosocial factors and measures of psychological distress were reported for immigrants and natives in three studies of the full general working population in Kingdom of spain [38], employees in a transportation visitor in Finland [17] and the general working population of Swedish women [87]. By contrast, stressors were more strongly associated with measures of psychological distress among natives than among immigrants in a German report of workers in a post service company [44], two Danish studies of cleaners [54] and elderly care workers [55] and a Finnish study of physicians [49].

Bullying or discrimination in the workplace and health (n = 12 studies; Table 3)

Non-Western immigrant health care workers [43], and immigrant employees in a transportation company [18], were more likely to written report bullying than natives. College levels of perceived discrimination amidst immigrant workers compared with natives have been observed in studies of the general working population in Spain [33, 41], the Czechia [36], Switzerland [48], and the UK [19, 91], and in United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland studies of ethnic minority nurses and teachers [51, 86], and in Swedish studies of immigrant women employed in a municipality [fifteen] and non-Nordic immigrants employed in elderly care [46].

Pertaining to research question 1B, a Spanish survey reported an association between piece of work-related discrimination and poor mental health and self-reported health (SRH) amongst immigrant workers [13]. A study of the general working population in the UK reported that the run a risk of mental disorders was highest among people from indigenous minorities who reported having received unfair treatment or racial insults [xix].

Employment conditions and wellness (n = 10 studies; Tabular array 4)

Studies of the general working population from Sweden [15] and Spain [21, 33, 73], accept plant that immigrants were more than likely to report having a temporary piece of work contract, or to be undocumented and working without a contract [75], whereas studies from Canada have found that recent immigrants were more likely to written report temporary employment than were natives [sixty, 72]. Employment precariousness (i.e., employment instability, depression wages, limited rights) was significantly college among immigrants than amidst Spanish natives [90]. Over-pedagogy, which is divers as a discrepancy between a person's educational attainment and the educational requirements of his or her occupation, was reported to be more than prevalent among workers from outside of Western Europe, compared with natives in the full general working population in Sweden [34].

Pertaining to enquiry question 1B, having no piece of work contract or a temporary contract [75] or precarious work situation [89] were all associated to the same extent with poor SRH and mental health in both immigrant and native Castilian workers. Beingness employed in a temporary job was more strongly related to having inability alimony amid Castilian natives than among immigrants [73], just was more strongly related to sickness presenteeism amidst immigrants than among natives [12]. A higher risk of poor mental health was observed among immigrants with illegal or temporary legal condition compared with those who had acquired Castilian citizenship [62]. Over-educated foreign-born workers from countries outside Western Europe had double the risk for poor SRH compared with over-educated native-born Swedish workers [34], and 4 years after inflow in Canada, immigrants experiencing whatever dimension of over-qualification were significantly more than likely to study a refuse in mental health [26], and had a higher risk of piece of work injuries requiring medical attention compared with not-recent and not over-educated immigrants [61].

Health problems, ill leave, disability and work injuries (north = 45 studies)

Studies addressing whether the prevalence of health problems is higher in immigrant workers than in native workers (research question 2A) have evaluated the following health indicators: SRH and mental distress (n = 17), sick leave or disability pension (n = 12) and work injuries (n = 16). Among the 45 studies, 9 examined whether differences pertaining to working conditions mediate the association between immigrant status and health problems [25, 35, 52] or ill leave and disability rates [23, 24, 28, 42, 73, 82] (inquiry question 2B).

Self-reported health (SRH) and mental distress (northward = 17 studies; Tabular array 5)

A higher risk of poor SRH among immigrants compared with natives, accept been reported in general working population studies in Sweden [35], Norway [82] and Spain [21, 25], and studies of cleaners [47] and elderly care workers [23] in Denmark. A written report of the full general working population from the Czech Democracy reported small differences in SRH between natives and immigrants [36]. Two studies compared SRH between groups of immigrant workers [58, 76].

Four surveys of the general working population in Espana reported college risk of mental health problems among immigrant women [25, 32, 89] or both immigrant men and women [38] compared with natives. Higher levels of mental health problems were also found amidst immigrants in surveys of the general working population in Sweden [35] and holland [52], a study of infirmary employees in Frg [69] and a written report of cleaners in Norway [84]. Iii studies have reported higher levels of exhaustion among groups of immigrant workers compared with natives [ten, 55, 87]. Even so, three other studies observed no significant increase in the risk of mental distress in immigrant workers [19, 44, 56].

Pertaining to research question 2B, differences relating to psychosocial working conditions and physical load were reported to have a pocket-sized or negligible issue on the risk of poor mental health or SRH among immigrants in a study of the full general working population in Sweden [35] and amidst immigrant women in the general working population in Spain [25]. In a report of the working population in the netherlands, lack of recovery opportunities at work, but non perceived work stress, deemed in role for higher levels of mental health problems in ethnic minority groups compared with natives [52]. In a Norwegian study of female cleaning personnel, aligning for psychosocial and organizational working conditions did non reduce the observed divergence in mental distress between natives and immigrants [84].

Sick leave and disability alimony (north = 12 studies; Table 6)

4 studies of the general working population in Norway [22, 42, 82, 83] and Sweden [81] showed that non-Western immigrants had more general sickness absence [42, 81,82,83] and pregnancy-related sick leave [22]. Nevertheless, compared with Norwegian natives, immigrant men from Northward America and Oceania had lower sickness absenteeism rates, and second-generation immigrants had similar sickness absence rates [83]. 2 studies from Kingdom of denmark reported that immigrants had similar [24] or lower [23] rates of sick leave than natives inside the same occupation. A Castilian follow-upwards study of native and immigrant patients treated by principal intendance physicians, observed a lower risk of sick exit amidst immigrants [74].

Nationwide register-based studies of the Swedish [45] and Norwegian [28] working population showed near double risk of disability pension among immigrant workers compared with natives, and a study from the Netherlands reported a more than double gamble of disability pension among Turkish scaffolders compared with natives in the aforementioned occupation [37]. By contrast, a nationwide study from Spain reported that immigrants had a lower probability of receiving disability pension than natives [73].

Pertaining to research question 2B, adjustment for occupation (4-digit code) in two studies of the full general working population in Norway reduced the observed higher gamble of sickness absence among immigrants compared with natives by 12% (in Eastern European immigrants) to 26% (in African immigrants) [42]. Aligning also decreased the difference in the average number of days on sick get out between immigrants and natives by about i-tertiary [82]. A report from Norway reported that the observed excess risk of using inability pension was largely explained past work factors and level of income, merely not by country of origin [28]. By dissimilarity, a written report from Spain reported a lower risk of use of disability alimony among immigrants despite the worse working conditions for immigrants [73].

Work-related injuries (n = 16 studies; Table vii)

A higher risk of fatal accidents in immigrants was reported in one study of insured workers in Espana (RR = 4.4; 95% CI 3.9–5.one in women and RR = half dozen.0; 95% CI 3.vi–nine.half dozen in men) [14]. A higher take a chance of non-fatal accidents in immigrants was reported in 2 register-based population studies in Espana and Denmark, respectively [14, 20]. Three survey studies of general working populations found that, compared to natives, the occurrence of self-reported occupational injuries was significantly higher in male person immigrants in Italy [67]; immigrant men in their starting time 5 years in Canada [71]; and immigrant workers in high-risk occupations in Canada [88]. Past contrast, a Finnish survey of jitney drivers reported a higher injury rate for Finnish than for immigrant drivers [66]. Two studies from Canada using aggregated injury data at the occupational level reported conflicting results in regard to whether immigrants were overrepresented in high-risk occupations [59, 78].

Six studies reported that immigrants are over-represented in register-based studies of patients treated for work injuries [29, 31, xl, 50, 65, 85]. The injury rates in immigrants ranged from 109.1 to 271.eight per 1000 non-EU illegally employed people compared with 65 per g for the general working population in Italy in 2004 [50]. A Swiss study of emergency unit of measurement patients reported that 66.4% of the injured workers were foreigners; this rate was twice that for the overall proportion of foreigners in Switzerland [forty]. The incidence of hospitalized ocular injuries per 100,000 was 134 in immigrants from the European union accession states versus ten in those of Irish origin in 2006–2007 [65], and the number of patients with a manus injury originating from the x new EU accretion states in 2004 was reported to increase markedly from 2000 to 2005. Two studies of patients with construction-related eye injuries [29] and workplace injuries requiring referral to a plastic surgery service [31] reported that 48 and 40% of the injuries, respectively, were in foreign-born workers; these workers represented 9% of the total workforce in Ireland. [sixteen]. A Norwegian study of occupational injuries registered in an emergency ward reported that thirty% of those with serious injuries had a non-Scandinavian language as their outset language; these workers represented 12% of the workforce [85].

Discussion

The aim of the nowadays paper was to use a systematic arroyo to explore the literature and determine whether working conditions and occupational wellness differ between immigrant and native workers in Europe and Canada.

The most robust result in the present analyses is the higher adventure of piece of work injuries in immigrant than in native workers in studies from different countries and with different designs (eastward.yard., occupational injury records, national surveys and patient records) [14, 20, 29, 31, 40, l, 65, 67, 71, 85, 88]. Notwithstanding, one study that compared immigrants and natives with similar jobs and work tasks (bus drivers) did not find a higher risk among immigrants [66]. Different study designs and the fact that many of the studies were based on patient samples without access to the population at chance make it difficult to compare the take chances estimates in all studies. Annals-based population studies are considered the gold standard for estimating injury rates in the general population; nevertheless, a mutual limitation in all the included studies was that these studies did non business relationship for illegally employed workers, likewise as legally workers, who were non found in the national registries. Nevertheless, our findings are consistent with the results from two previous reviews based primarily on studies from the United States (U.S.) [8, 14]. Preventing work injuries in immigrant workers should take a loftier priority at both the government and enterprise levels.

Across a large number of survey studies, our analyses consistently show that the prevalence rates of bullying [18, 43] and perceived discrimination [fifteen, xix, 36, 41, 46, 48, 51, 86, 91] were higher in immigrants than in natives. Notwithstanding, the dissimilar definitions and measures of bullying and discrimination used in these studies rules out the possibility of comparing prevalence estimates. Immigrants do not generally announced to experience poorer psychosocial working conditions than natives inside similar occupational groups, and psychosocial working weather announced to be equally important for health in both immigrants and natives [17, 38, 44, 49, 54, 55, 87]. Nevertheless, results of studies of the general working population show that immigrants are more than likely to exist employed in jobs with a lower level of autonomy and opportunities for evolution [35, 39, 77, 80]. In improver, employment conditions such as temporary work [15, 21, 33, 73], lack of work contracts [33] and over-qualification [34] are prevalent and may be of import work factors to take into account, particularly in studies of recent immigrants [26, 72]. Farther studies are needed to replicate these results in different countries and groups of immigrants.

Only a few studies have addressed the physical and chemical working surround of immigrant workers. We did not identify any studies of the wellness consequences related to physical and chemical exposures in the workplace. Such health consequences may manifest several years later the exposure and are therefore non straightforward to investigate, which may partly explain the lack of studies in this field. A previous review reported that studies of exposure and wellness issues tended to focus on specific exposure in specific occupational groups, such as pesticide exposure amidst agricultural workers [8]. However, these studies were conducted in the U.S. Thus, the nowadays study shows that physical or chemical exposures among immigrant workers have been neglected in the European research literature. One possible explanation is that studies of exposure to concrete or chemical factors at piece of work may take focused on the exposure and effect in sure occupational groups, every bit in the U.S., without reporting other characteristics of the exposed groups, such every bit immigrant status.

Our study shows that immigrant workers report higher levels of poor SRH [21, 23, 25, 35, 47, 82] and mental distress [ten, 25, 32, 35, 52, 55, 69, 84, 87, 89] than practice natives, which is consistent with the findings of two previous reviews [115, 116]. Our analysis likewise showed that near [28, 37, 42, 45, 81,82,83] but not all studies [23, 24, 73] take reported a higher risk of sick go out and disability pension among immigrants compared with natives. The bear witness that occupational factors may partly contribute to the excess risk of sick get out and disability pension observed among immigrants is sparse, although a few Scandinavian studies support this observation [28, 42, 82]. Yet, differences pertaining to working conditions were reported to have a pocket-sized or negligible bear upon on the increased risk of poor mental health or SRH among immigrants compared with natives in studies from Scandinavia [35, 84], Spain [25] and the Netherland [52].

Methodological shortcomings in the primary manufactures

Our systematic review indicated a need for more high-quality epidemiological studies investigating the relationship betwixt working weather condition and occupational health; that is, in that location are few prospective accomplice studies that take diverse workplace characteristics, immigrant status and baseline health into account.

Most of the included studies of immigrant workers were cross-exclusive and relied on cocky-report. Although self-reported information are an important source of information nearly the working surroundings and wellness in the population, both cognitive and situational factors may influence the validity of the data. Several of the studies used non-validated instruments to measure piece of work exposure or provided petty information about the items or instruments used to mensurate the variables of interest. Moreover, different factors (e.grand., language barriers and differences in semantic meanings, expectations and frames of reference) tin can influence how immigrants evaluate or appraise their work environment and understand and interpret the questions and survey context. In improver, a lack of consistency in the assessment methods and instruments brand it difficult to compare risk and prevalence beyond studies of immigrant workers in different study contexts.

Another important consideration is the representativeness of the samples recruited. Immigrants are a heterogeneous grouping, and individual immigrants may come from different countries, migrate for unlike reasons, live in different recipient countries and work permanently or for a limited period. Over-sampling is often required to yield sufficient statistical information, and many studies have included modest sample sizes that may not have been drawn randomly. Moreover, the lack of access to some populations, such equally immigrant workers on short stays or undocumented migrants, is another obstruction.

Nearly studies of immigrant workers' occupational exposures and health evaluated in our review focused on differences between immigrants and the native population in the host country; these provide some insights into differences and similarities in occupational exposure and present health status. However, factors such every bit the diverseness of immigrants in terms of their historic period, sexual practice, country of origin and destination, socio-economic status, the type of migration influence the possibility to perform simple comparisons of the occupational wellness status between immigrants and natives [7, 117]. Moreover, the "healthy immigrant issue" hypothesis suggesting that migrants are initially healthier than non-migrant populations due to the selection of healthy migrants at migration, but later deterioration of effect considering of exposure to risks in host countries, further complicates this issue [117, 118] . Thus, the lack of prospective studies that have included factors that can impact wellness at different stages before, during and after migration limits the ability to decide the extent to which factors in the piece of work surroundings, together with other gamble factors, may contribute to the take chances of disease and disease.

Limitations and strengths of the current review

Few studies accept evaluated the occupational health risks of immigrant populations. This is the commencement systematic review to summarize the literature on all aspects of working conditions and occupational health in immigrant workers in Europe and Canada. We searched the literature using a number of databases and hand searched the reference list of all the included studies to minimize the risk of missing of import studies. The selection of manufactures in English or Nordic languages and our strict inclusion criteria of original, quantitative, peer-reviewed studies may accept led u.s. to overlook relevant documentation published in reports, books or websites that may shed low-cal on this topic. Chiefly, the study population in this review represents a narrow spectrum of socio-economic and cultural environments, which makes it impossible to generalize the results to immigrant workers in all parts of Europe or in other parts of the globe.

1 limitation of this review is the heterogeneity of the methodology used in the included studies. Big differences were observed between the studies in terms of sample size, recruitment methods and cess of working atmospheric condition and occupational health, and these variations restrict our ability to compare and combine the findings of individual studies. Hence, when accounting for the large number of studies with different study aims, populations and methodological approaches, the results will inevitably be a simplification, summary and option of information and knowledge. Nevertheless, we believe that some full general conclusions can be drawn based on the current knowledge nearly the working weather condition and health of immigrants.

Decision

The overall show to show that immigrant workers are more exposed to physical or chemical hazards and poor psychosocial working weather condition than natives in Europe and Canada is very express. Nevertheless, the prevalence of bullying and perceived discrimination is consistently higher among immigrant than among native workers. Immigrants have a college risk of work-related injuries than practice natives. The bachelor evidence supports the inference that immigrant workers are disadvantaged in terms of cocky-perceived health and mental distress compared with the native population. However, the evidence to conclude that the working atmospheric condition are a potential mediator of the clan between immigrant status and these health outcomes is very limited. Even so, a few studies from the Scandinavian countries support the idea that controlling for occupational factors may partly mitigate the differences in risk of sick leave and disability pension betwixt non-Western immigrants and natives.

Knowledge of the working conditions and occupational health of immigrant and ethnic minorities is of import for initiating preventive and integrational efforts. However, this is challenging because of shortcomings in the available data, heterogeneity of immigrant populations, uncertainty virtually the validity of instruments and the lack of prospectively designed cohort studies. These challenges underscore the importance of collecting information on working conditions and wellness more systematically, particularly amidst groups that are presumed to be at greater risk of being employed in high-chance jobs.

To understand farther the associations betwixt working conditions, health and immigrant status, and to facilitate cross-country comparisons in the European context, big-calibration studies that focus on different aspects such equally immigrants' cultural and socio-economical backgrounds, language skills and fourth dimension lived in the host country are needed, equally are investigations that are culturally appropriate and employ instruments translated into the mother natural language of the target groups of immigrants. Tools and procedures that include immigrants and ethnic minorities in the existing information collection processes, such every bit censuses, national statistics and health surveys are too needed.

Many aspects of working weather and occupational health related to immigrant movements remain to exist investigated. There are indications of the over-representation of immigrants in depression-skilled, high-take chances transmission jobs, which require confirmation through the analysis of valid empirical data. In addition, there is a lack of information regarding unsettled and undocumented immigrant workers. This thing is complicated past short-term, circular and return migration, which creates difficulties for data drove and reliable assessment of occupational health bug among immigrant workers.

References

-

OECD/EU. Recruiting Immigrant Workers: Europe: OECD Publishing; 2016.

-

ILO. ILO Global estimates of migrant workers and migrant domestic workers: results and Methodology. In: International Labour Office. Geneva: ILO; 2015. p. 2015.

-

Marmot M, Allen J, Bong R, Bloomer Due east, Goldblatt P. WHO European review of social determinants of wellness and the health carve up. Lancet. 380(9846):1011–29.

-

Stiglitz JE, Sen A, Fitoussi J-P. Report past the commission on the measurement of economical performance and social progress. Paris; 2010. http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/118025/118123/Fitoussi+Commission+study.

-

Takala J, Urrutia M, Hämäläinen P, Saarela KL. Global and European work surround—numbers, trends, and strategies. Scand J Work Environ Wellness. 2009;35:15.

-

Benach J, Muntaner C, Delclos C, Menéndez M, Ronquillo C. Migration and "low-skilled" Workers in Destination Countries. PLoS Med. 2011;8(6):e1001043.

-

Rechel B, Mladovsky P, Ingleby D, Mackenbach JP, McKee One thousand. Migration and health in an increasingly diverse Europe. Lancet. 2013;381(9873):1235–45.

-

Ahonen EQ, Benavides FG, Benach J. Immigrant populations, piece of work and health--a systematic literature review. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2007;33(two):96–104.

-

Mattioli Due south, Zanardi F, Baldasseroni A, Schaafsma F, Cooke RMT, Mancini Grand, Fierro Thousand, Santangelo C, Farioli A, Fucksia South, et al. Search strings for the written report of putative occupational determinants of disease. Occup Environ Med. 2010;67(7):436–43.

-

Aalto AM, Heponiemi T, Keskimaki I, Kuusio H, Hietapakka 50, Lamsa R, Sinervo T, Elovainio Grand. Employment, psychosocial work environment and well-existence among migrant and native physicians in Finnish health care. Eur J Pub Health. 2014;24(3):445–51.

-

Agudelo-Suarez AA, Benavides FG, Felt Due east, Ronda-Perez Eastward, Vives-Cases C, Garcia AM. Sickness presenteeism in Spanish-born and immigrant workers in Espana. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:791.

-

Agudelo-Suarez AA, Ronda Eastward, Vazquez-Navarrete ML, Garcia AM, Martinez JM, Benavides FG. Impact of economic crisis on mental health of migrant workers: what happened with migrants who came to Kingdom of spain to work? Int J Public Wellness. 2013;58(iv):627–31.

-

Agudelo-Suarez AA, Ronda-Perez Due east, Gil-Gonzalez D, Vives-Cases C, Garcia AM, Ruiz-Frutos C, Felt E, Benavides FG. The effect of perceived discrimination on the health of immigrant workers in Spain. BMC Public Health. 2011;eleven:652.

-

Ahonen EQ, Benavides FG. Chance of fatal and non-fatal occupational injury in foreign workers in Espana. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(5):424–6.

-

Akhavan Southward, Bildt C, Wamala S. Work-related wellness factors for female person immigrants in Sweden. Work. 2007;28(2):135–43.

-

Alexe DM, Petridou Eastward, Dessypris Northward, Skenderis N, Trichopoulos D. Characteristics of farm injuries in Greece. J Agric Saf Health. 2003;nine(3):233–40.

-

Bergbom B, Kinnunen U. Immigrants and host nationals at work: associations of co-worker relations with employee well-being. Int J Intercult Relat. 2014;43:165–76.

-

Bergbom B, Vartia-Vaananen M, Kinnunen U. Immigrants and natives at work: exposure to workplace bullying. Employee Relations. 2015;37(ii):158–75.

-

Bhui Thousand, Stansfeld S, McKenzie One thousand, Karlsen Southward, Nazroo J, Weich S. Racial/indigenous discrimination and common mental disorders among workers: findings from the EMPIRIC study of ethnic minority groups in the United kingdom. Am J Public Wellness. 2005;95(iii):496–501.

-

Biering K, Lander F, Rasmussen Thousand. Work injuries amidst migrant workers in Kingdom of denmark. Occup Environ Med. 2016;74(4):235–42.

-

Borrell C, Muntaner C, Sola J, Artazcoz L, Puigpinos R, Benach J, Noh Southward. Clearing and cocky-reported health status by social class and gender: the importance of material deprivation, piece of work arrangement and household labour. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62(v):e7.

-

Brekke I, Berg JE, Sletner 50, Jenum AK. Doctor-certified sickness absence in first and 2d trimesters of pregnancy amid native and immigrant women in Norway. Scand J Public Health. 2013;41(two):166–73.

-

Carneiro IG, Ortega A, Borg Five, Hogh A. Health and sickness absence in Denmark: a study of elderly-care immigrant workers. J Immigr Health. 2010;12(ane):43–52.

-

Carneiro IG, Rasmussen CDN, Jorgensen MB, Flyvholm MA, Olesen K, Madeleine P, Ekner D, Sogaard K, Holtermann A. The association betwixt health and sickness absence among Danish and not-western immigrant cleaners in Denmark. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2013;86(4):397–405.

-

Cayuela A, Malmusi D, Lopez-Jacob MJ, Gotsens M, Ronda E. The impact of education and socioeconomic and occupational atmospheric condition on self-perceived and mental health inequalities among immigrants and native Workers in Spain. J Immigr Minor Health. 2015;17(half-dozen):1906–10.

-

Chen C, Smith P, Mustard C. The prevalence of over-qualification and its association with health status amid occupationally active new immigrants to Canada. Ethn Wellness. 2010;15(six):601–19.

-

Chowhan J, Zeytinoglu IU, Cooke GB. Immigrants and job satisfaction: do high functioning work systems play a office? Econ Ind Democracy. 2016;37(4):690–715.

-

Claussen B, Dalgard OS, Bruusgaard D. Inability pensioning: tin indigenous divides exist explained by occupation, income, mental distress, or health? Scand J Public Wellness. 2009;37(4):395–400.

-

Connell PP, Saddak T, Harrison I, Kelly S, Bobart A, McGettrick P, Collum LT. Structure-related eye injuries in Irish gaelic nationals and not-nationals: attitudes and strategies for prevention. Ir J Med Sci. 2007;176(1):11–4.

-

Cross C, Turner T. Immigrant experiences of fairness at work in Ireland. Econ Ind Democracy. 2013;34(4):575–95.

-

Davidson CC, Orr DJ. Occupational injuries in foreign-national workers presenting to St James'southward hospital plastic surgery service. Ir Med J. 2009;102(iv):108–10.

-

Del Amo J, Jarrin I, Garcia-Fulgueiras A, Ibanez-Rojo V, Alvarez D, Rodriguez-Arenas MA, Garcia-Pina R, Fernandez-Liria A, Garcia-Ortuzar V, Diaz D, et al. Mental health in Ecuadorian migrants from a population-based survey: the importance of social determinants and gender roles. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2011;46(11):1143–52.

-

Diaz-Serrano 50. Immigrants, natives and job quality: evidence from Spain. Int J Manpow. 2013;34(7):753–75.

-

Dunlavy Air conditioning, Garcy AM, Rostila M. Educational mismatch and health status amidst foreign-born workers in Sweden. Soc Sci Med. 2016;154:36–44.

-

Dunlavy AC, Rostila Thousand. Health inequalities amid workers with a foreign groundwork in Sweden: exercise working conditions thing? Int J Environ Res Public Wellness. 2013;10(7):2871–87.

-

Dzurova D, Drbohlav D. Gender inequalities in the health of immigrants and workplace discrimination in Czechia. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:480425.

-

Elders LA, Burdorf A, Ory FG. Ethnic differences in disability gamble between Dutch and Turkish scaffolders. J Occup Health. 2004;46(5):391–seven.

-

Font A, Moncada South, Benavides FG. The human relationship between immigration and mental health: what is the role of workplace psychosocial factors. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2012;85(7):801–6.

-

Font A, Moncada S, Llorens C, Benavides FG. Psychosocial factor exposures in the workplace: differences between immigrants and Spaniards. Eur J Pub Health. 2012;22(v):688–93.

-

Frickmann F, Wurm B, Jeger 5, Lehmann B, Zimmermann H, Exadaktylos AK. 782 consecutive construction work accidents: who is at risk? A 10-year analysis from a Swiss academy hospital trauma unit. Swiss Med Wkly. 2012;142:w13674.

-

Gil-Gonzalez D, Vives-Cases C, Borrell C, Agudelo-Suarez AA, Davo-Blanes MC, Miralles J, Alvarez-Dardet C. Racism, other discriminations and furnishings on health. J Immigr Wellness. 2014;16(2):301–ix.

-

Hansen HT, Holmas TH, Islam MK, Naz G. Sickness absence among immigrants in Norway: does occupational disparity affair? Eur Sociol Rev. 2014;30(ane):1–12.

-

Hogh A, Carneiro IG, Giver H, Rugulies R. Are immigrants in the nursing manufacture at increased risk of bullying at work? A one-year follow-upwardly study. Scand J Psychol. 2011;52(1):49–56.

-

Hoppe A. Psychosocial working conditions and well-being amid immigrant and German language low-wage workers. J Occup Health Psychol. 2011;sixteen(2):187–201.

-

Johansson B, Helgesson Thousand, Lundberg I, Nordquist T, Leijon O, Lindberg P, Vingard E. Work and health among immigrants and native swedes 1990-2008: a annals-based study on hospitalization for common potentially work-related disorders, disability pension and bloodshed. BMC Public Wellness. 2012;12:845.

-

Jonson H, Giertz A. Migrant Care Workers in Swedish Elderly and Disability Care: are they disadvantaged? J Ethn Migr Stud. 2013;39(5):809–25.

-

Jorgensen MB, Rasmussen CD, Carneiro IG, Flyvholm MA, Olesen Chiliad, Ekner D, Sogaard K, Holtermann A. Health disparities between immigrant and Danish cleaners. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2011;84(vi):665–74.

-

Krings F, Johnston C, Binggeli South, Maggiori C. Selective incivility: immigrant groups experience subtle workplace discrimination at different rates. Cultur Divers Indigenous Modest Psychol. 2014;xx(four):491–eight.

-

Kuusio H, Heponiemi T, Vanska J, Aalto AM, Ruskoaho J, Elovainio M. Psychosocial stress factors and intention to leave job: differences between foreign-born and Finnish-built-in general practitioners. Scand J Public Wellness. 2013;41(4):405–eleven.

-

Mastrangelo G, Rylander R, Buja A, Marangi 1000, Fadda Due east, Fedeli U, Cegolon L. Work related injuries: estimating the incidence among illegally employed immigrants. BMC Res Notes. 2010;3:331.

-

Miller GV, Travers CJ. Ethnicity and the feel of work: job stress and satisfaction of minority indigenous teachers in the Great britain. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2005;17(five):317–27.

-

Nieuwenhuijsen Yard, Schene AH, Stronks K, Snijder MB, Frings-Dresen MH, Sluiter JK. Do unfavourable working conditions explain mental health inequalities between ethnic groups? Cross-sectional data of the HELIUS study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:805.

-

Olesen K, Carneiro IG, Jorgensen MB, Flyvholm MA, Rugulies R, Rasmussen CD, Sogaard K, Holtermann A. Psychosocial work surround amongst immigrant and Danish cleaners. Int Arch Occup Environ Wellness. 2012;85(1):89–95.

-

Olesen Yard, Carneiro IG, Jorgensen MB, Rugulies R, Rasmussen CD, Sogaard K, Holtermann A, Flyvholm MA. Associations between psychosocial work environment and hypertension among non-western immigrant and Danish cleaners. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2012;85(vii):829–35.

-

Ortega A, Gomes Carneiro I, Flyvholm MA. A descriptive study on immigrant workers in the elderly care sector. J Immigr Wellness. 2010;12(5):699–706.

-

Pasca R, Wagner SL. Occupational stress, mental health and satisfaction in the Canadian multicultural workplace. Soc Indic Res. 2012;109(3):377–93.

-

Perez-Carceles MD, Medina Doc, Perez-Flores D, Noguera JA, Pereniguez JE, Madrigal M, Luna A. Screening for hazardous drinking in migrant workers in southeastern Spain. J Occup Health. 2014;56(1):39–48.

-

Pikhart H, Drbohlav D, Dzurova D. The self-reported health of legal and illegal/irregular immigrants in the Czechia. Int J Public Health. 2010;55(5):401–11.

-

Premji Due south, Duguay P, Messing Chiliad, Lippel Thou. Are immigrants, ethnic and linguistic minorities over-represented in jobs with a high level of compensated adventure? Results from a Montreal, Canada study using demography and workers' compensation data. Am J Ind Med. 2010;53(9):875–85.

-

Premji S, Lewchuk W. Racialized and gendered disparities in occupational exposures among Chinese and white workers in Toronto. Ethn Health. 2014;nineteen(5):512–28.

-

Premji S, Smith PM. Education-to-job mismatch and the run a risk of piece of work injury. Inj Prev. 2013;nineteen(2):106–11.

-

Robert M, Martinez JM, Garcia AM, Benavides FG, Ronda East. From the smash to the crisis: changes in employment conditions of immigrants in Spain and their effects on mental wellness. Eur J Pub Health. 2014;24(iii):404–9.

-

Ronda E, Agudelo-Suarez AA, Garcia AM, Lopez-Jacob MJ, Ruiz-Frutos C, Benavides FG. Differences in exposure to occupational wellness risks in Castilian and foreign-born workers in Spain (ITSAL project). J Immigr Health. 2013;15(1):164–71.

-

Ronda EP, Benavides FG, Levecque Grand, Dearest JG, Felt E, Van Rossem R. Differences in working weather and employment arrangements among migrant and non-migrant workers in Europe. Ethn Health. 2012;17(six):563–77.

-

Saeed A, Khan I, Dunne O, Stack J, Beatty S. Ocular injury requiring hospitalisation in the south east of Republic of ireland: 2001–2007. Injury. 2010;41(ane):86–91.

-

Salminen S, Vartia Thousand, Giorgiani T. Occupational injuries of immigrant and Finnish charabanc drivers. J Saf Res. 2009;40(three):203–5.

-

Salvatore MA, Baglio G, Cacciani L, Spagnolo A, Rosano A. Piece of work-related injuries among immigrant workers in Italy. J Immigr Wellness. 2013;fifteen(ane):182–7.

-

Sattler T, Tobbia D, O'Shaughnessy One thousand. Mitt injuries in strange labour workers in an Irish university hospital. Tin J Plast Surg. 2009;17(1):22–4.

-

Sieberer M, Maksimovic S, Ersoz B, Machleidt W, Ziegenbein M, Calliess IT. Depressive symptoms in showtime-and second-generation migrants: a cross-sectional study of a multi-indigenous working population. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2012;58(6):605–13.

-

Smith PM, Chen C, Mustard C. Differential risk of employment in more physically demanding jobs amid a contempo cohort of immigrants to Canada. Inj Prev. 2009;15(four):252–eight.

-

Smith PM, Mustard CA. Comparison the risk of piece of work-related injuries between immigrants to Canada and Canadian-born labour marketplace participants. Occup Environ Med. 2009;66(6):361–vii.

-

Smith PM, Mustard CA. The unequal distribution of occupational wellness and safety risks amid immigrants to Canada compared to Canadian-born labour market participants: 1993-2005. Saf Sci. 2010;48(x):1296–303.

-

Sole M, Diaz-Serrano L, Rodriguez 1000. Disparities in work, chance and wellness betwixt immigrants and native-born Spaniards. Soc Sci Med. 2013;76(1):179–87.

-

Soler-Gonzalez J, Serna MC, Bosch A, Ruiz MC, Huertas Eastward, Rue Thousand. Sick leave amongst native and immigrant workers in Kingdom of spain--a 6-month follow-up study. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2008;34(vi):438–43.

-

Sousa Due east, Agudelo-Suarez A, Benavides FG, Schenker Thousand, Garcia AM, Benach J, Delclos C, Lopez-Jacob MJ, Ruiz-Frutos C, Ronda-Perez Eastward, et al. Immigration, work and health in Espana: the influence of legal status and employment contract on reported health indicators. Int J Public Wellness. 2010;55(5):443–51.

-

Subedi RP, Rosenberg MW. Determinants of the variations in cocky-reported health status among contempo and more than established immigrants in Canada. Soc Sci Med. 2014;115:103–10.

-

Sundquist J, Ostergren PO, Sundquist K, Johansson SE. Psychosocial working conditions and self-reported long-term illness: a population-based study of Swedish-built-in and foreign-born employed persons. Ethn Health. 2003;viii(four):307–17.

-

Tiagi R. Are immigrants in Canada over-represented in riskier jobs relative to Canadian-born labor market participants? Am J Ind Med. 2015;58(ix):933–42.

-

Tiagi R. Intergenerational differences in occupational injury and fatality rates among Canada's immigrants. Occup Med. 2016;66(nine):743–50.

-

Tora I, Martinez JM, Benavides FG, Leveque Chiliad, Ronda E. Upshot of economic recession on psychosocial working conditions by workers' nationality. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2015;21(iv):328–32.

-

Bengtsson T, Scott 1000. Immigrant consumption of sickness benefits in Sweden, 1982–1991. J Socio-Econ. 2006;35(three):440–57.

-

Brekke I, Schøne P. Long sickness absence differences betwixt natives and immigrant workers: the role of differences in cocky-reported wellness. JIMI. 2014;15(two):217–35.

-

Dahl S-Å, Hansen H-T, Olsen KM. Sickness absence among immigrants in Norway, 1992—2003. Acta Sociologica. 2010;53(1):35–52.

-

Gamperiene M, Nygård JF, Sandanger I, Wærsted M, Bruusgaard D. The impact of psychosocial and organizational working conditions on the mental health of female cleaning personnel in Kingdom of norway. J Occup Med Toxicol. 2006;1(1):24.

-

Gravseth HM, Lund J, Wergeland E. Arbeidsskader behandlet ved Legevakten i Oslo og Ambulansetjenesten [occupational injuries in Oslo: a written report of occupational injuries treated by the Oslo emergency Ward and Oslo ambulance service]. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2003;123(fifteen):2060–four.

-

Shields MA, Price SW. Racial harassment, job satisfaction and intentions to quit: prove from the British nursing profession. Economica. 2002;69(274):295–326.

-

Sundin O, Soares J, Grossi G, Macassa K. Burnout among foreign-born and native Swedish women: a longitudinal study. Women Health. 2011;51(vii):643–60.

-

Thurston W, Verhoef Thou. Occupational injury among immigrants. JIMI. 2003;4(1):105–23.

-

Vives A, Amable Chiliad, Ferrer M, Moncada South, Llorens C, Muntaner C, Benavides FG, Benach J. Employment precariousness and poor mental health: prove from Spain on a new social determinant of wellness. J Environ Public Health. 2013;2013:978656.

-

Vives A, Vanroelen C, Amable M, Ferrer M, Moncada S, Llorens C, Muntaner C, Benavides FG, Benach J. Employment precariousness in Kingdom of spain: prevalence, social distribution, and population-attributable hazard per centum of poor mental health. Int J Health Serv. 2011;41(4):625–46.

-

Wadsworth East, Dhillon K, Shaw C, Bhui Thou, Stansfeld S, Smith A. Racial discrimination, ethnicity and work stress. Occup Med. 2007;57(1):xviii–24.

-

Dumortier P, Gocmen A, Laurent G, Manco A, De Vuyst P. The role of environmental and occupational exposures in Turkish immigrants with fibre-related affliction. Eur Respir J. 2001;17(5):922–7.

-

Merler E, Bizzotto R, Calisti R, Cavone D, De Marzo N, Gioffre F, Mabilia T, Marcolina D, Musti K, Munafo MG, et al. Mesotheliomas amidst Italians, returned to the home country, who worked when migrant at a cement-asbestos factory in Switzerland. Soz Praventivmed. 2003;48(1):65–9.

-

Adhikari R, Melia KM. The (mis)management of migrant nurses in the Uk: a sociological study. J Nurs Manag. 2015;23(3):359–67.

-

Agudelo-Suarez A, Gil-Gonzalez D, Ronda-Perez E, Porthe 5, Paramio-Perez G, Garcia AM, Gari A. Discrimination, work and health in immigrant populations in Spain. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(ten):1866–74.

-

Ahonen EQ, Lopez-Jacob MJ, Vazquez ML, Porthe 5, Gil-Gonzalez D, Garcia AM, Ruiz-Frutos C, Benach J, Benavides FG, Project I. Invisible work, unseen hazards: the health of women immigrant household service workers in Spain. Am J Ind Med. 2010;53(4):405–16.

-

Ahonen EQ, Porthe V, Vazquez ML, Garcia AM, Lopez-Jacob MJ, Ruiz-Frutos C, Ronda-Perez E, Benach J, Benavides FG, Project I. A qualitative study about immigrant workers' perceptions of their working weather in Spain. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63(xi):936–42.

-

Chen SI, Skillen DL. Promoting personal safety of building service workers: issues and challenges. AAOHN J. 2006;54(6):262–9.

-

Dean JA, Wilson Thousand. 'Instruction? Information technology is irrelevant to my chore now. It makes me very depressed ...': exploring the wellness impacts of under/unemployment among highly skilled recent immigrants in Canada. Ethn Wellness. 2009;14(two):185–204.

-

Facey ME. The health effects of taxi driving - the case of visible minority drivers in Toronto. Tin J Public Wellness. 2003;94(iv):254–7.

-

Friberg JH, Arnholtz J, Eldring Fifty, Hansen NW, Thorarins F. Nordic labour market institutions and new migrant workers: smoothen migrants in Oslo, Copenhagen and Reykjavik. Europ J Ind Relat. 2014;20(1):37–53.

-

Galon T, Briones-Vozmediano E, Agudelo-Suarez AA, Felt EB, Benavides FG, Ronda Eastward. Agreement sickness presenteeism through the feel of immigrant workers in a context of economic crunch. Am J Ind Med. 2014;57(8):950–9.

-

Hviid K, Smith LH, Frydendall KB, Flyvholm MA. Visibility and social recognition equally psychosocial piece of work environment factors among cleaners in a multi-ethnic workplace intervention. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2012;10(1):85–106.

-

Jensen FW, Frydendall KB, Flyvholm MA. Vocational preparation courses as an intervention on change of work practise among immigrant cleaners. Am J Ind Med. 2011;54(11):872–84.

-

Kosny A, MacEachen E, Lifshen M, Smith P, Jafri GJ, Neilson C, Pugliese D, Shields J. Frail dances: immigrant workers' experiences of injury reporting and claim filing. Ethn Wellness. 2012;17(3):267–xc.

-

Lopez-Jacob MJ, Safont EC, Garcia AM, Gari A, Agudelo-Suarez A, Gil A, Benavides FG. Participation and influence of migrant workers on working conditions: a qualitative arroyo. New Solutions. 2010;twenty(2):225–38.

-

Nortvedt Fifty, Hansen HP, Kumar BN, Lohne V. Caught in suffering bodies: a qualitative written report of immigrant women on long-term sick leave in Norway. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24(21–22):3266–75.

-

Nortvedt L, Lohne V, Kumar BN, Hansen HP. A lonely life--a qualitative written report of immigrant women on long-term ill go out in Norway. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;54:54–64.

-

Porthe Five, Ahonen E, Vazquez ML, Pope C, Agudelo AA, Garcia AM, Amable M, Benavides FG, Benach J, Project I. Extending a model of precarious employment: a qualitative report of immigrant workers in Spain. Am J Ind Med. 2010;53(4):417–24.

-

Premji S, Messing Yard, Lippel K. Broken English language, broken bones? Mechanisms linking linguistic communication proficiency and occupational health in a Montreal garment manufacturing plant. Int J Health Serv. 2008;38(one):1–xix.

-

Ronda E, Briones-Vozmediano E, Galon T, Garcia AM, Benavides FG, Agudelo-Suarez AA. A qualitative exploration of the impact of the economic recession in Kingdom of spain on working, living and health conditions: reflections based on immigrant workers' experiences. Health Look. 2016;19(2):416–26.

-

Sarli A. The psycho-social malaise of migrant individual carers in Italia: a rampant, simply subconscious health demand. Acta Bio-Medica de l Ateneo Parmense. 2014;85(iii):62–73.

-

Smith LH, Hviid K, Frydendall KB, Flyvholm MA. Improving the psychosocial work surroundings at multi-ethnic workplaces: a multi-component intervention strategy in the cleaning industry. Int J Environ Res Public Wellness. 2013;10(10):4996–5010.

-

Weishaar HB. Consequences of international migration: a qualitative study on stress amongst smooth migrant workers in Scotland. Public Health. 2008;122(xi):1250–half-dozen.

-

Nielsen SS, Krasnik A. Poorer self-perceived wellness among migrants and ethnic minorities versus the majority population in Europe: a systematic review. Int J Public Health. 2010;55(five):357–71.

-

Lindert J, Ehrenstein OS, Priebe South, Mielck A, Brähler Eastward. Depression and anxiety in labor migrants and refugees – a systematic review and meta-assay. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(2):246–57.

-

Domnich A, Panatto D, Gasparini R, Amicizia D. The "salubrious immigrant" effect: does it exist in Europe today? IJPH. 2012;nine(3):e7532. https://ijphjournal.it/article/view/7532/6791.

-

Moullan Y, Jusot F. Why is the 'healthy immigrant effect' dissimilar between European countries? Eur J Pub Health. 2014;24(Suppl 1):fourscore–6.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Nordic Quango of Ministers for fiscal support and Benedicte Mohr for communication on literature search strategies.

Funding

The present systematic review was supported past the Nordic Council of Ministers (grant # 16222). The funding trunk had no part in the in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of information and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included inside the commodity (and its Additional files).

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

TS initiated the study and coordinated the piece of work. TT, ISM, KBV, BB, AA, BJ, MB, KH, MAF and TS contributed to the processes of defining the criteria for the inclusion and exclusion of studies, reviewing and assessing the chief studies, discussing findings, drawing conclusions too as the completion of the manuscript. TS drafted the manuscript. TS agrees to act as guarantor for the newspaper. All authors have read and approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Corresponding writer

Ethics declarations

Ethics approving and consent to participate

Non applicative.

Consent for publication

Not applicable, no study subjects involved.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher'south Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Boosted files

Boosted file one:

Search profiles. (DOCX 15 kb)

Additional file 2:

Working conditions and occupational health among immigrant workers: The information (authors; country, year of publication; aims of the report; report design; sample description, working weather; health outcomes, summary of chief results and general methodological comments) extracted from the articles. (DOCX 61 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed nether the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution four.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/four.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided y'all give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and point if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/i.0/) applies to the information made available in this commodity, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this commodity

Sterud, T., Tynes, T., Mehlum, I.S. et al. A systematic review of working weather and occupational wellness among immigrants in Europe and Canada. BMC Public Health 18, 770 (2018). https://doi.org/x.1186/s12889-018-5703-iii

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/x.1186/s12889-018-5703-iii

Keywords

- Emigrants and immigrants

- Labour migrant

- Migrant worker

- Occupations

- Occupational injury

- Occupational safety and health

- Review

- Systematic review

- Work

Source: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-018-5703-3